Years ago while visiting friends in Raleigh, they took me out for dinner. The husband part of the couple was terribly excited about the place (I might remember his wife rolling her eyes), not because of the food (which I don’t remember at all), but because they served grappa (which I remember distinctly).

I hadn’t had the pleasure before, and it certainly wasn’t a pleasure then.

Looking back, I’m not even sure if he liked it himself, or if he really just enjoyed seeing the expressions on others’ faces as they choked down this foul-tasting drink.

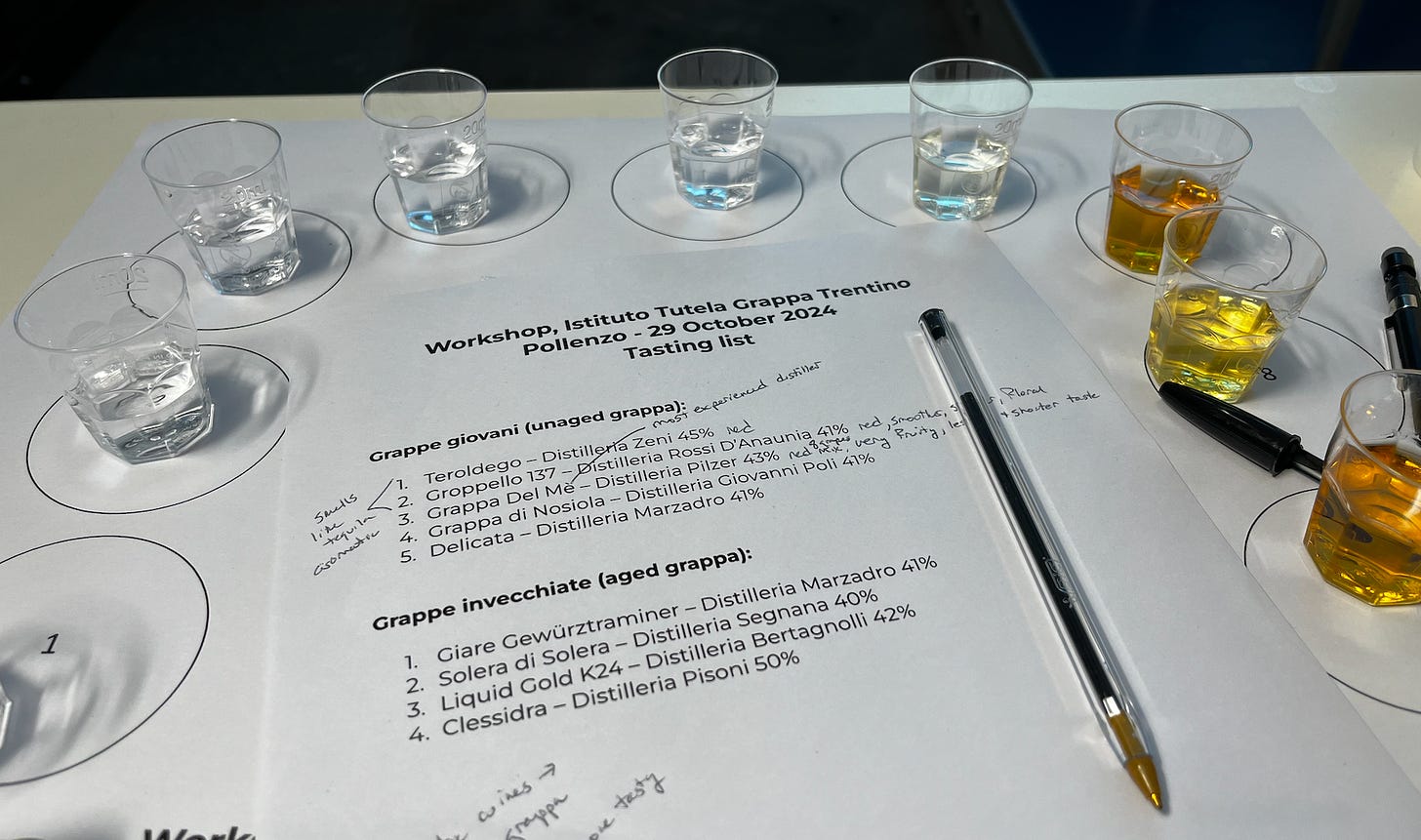

Decades later I’ve participated in not one, but two grappa tastings here in Italy, and toured the production facility and met the family making Nonino Grappa since 1897. And I’ve learned that while some grappa does indeed have a less-than-enjoyable flavor, others can be quite tasty, while some, well, still require an acquired taste.

It’s really a matter of telling heads from tails. (This pun will have more meaning as you continue reading, I promise.)

Grappa, like so many foods and beverages in the world, is a “peasant” invention, made by distilling marc, or pomace, the skins, seeds, and stalk leftover from wine production. After the grapes have given most of their goodness to the wine, they still have some sugar to ferment, if you know how to coax it out.

Also, you need to understand that grappa is Italian, and made from grapes. If it comes from anywhere else, or is made from anything else, you’ll have to take that up with EEC Regulation n. 1579, which came into play in 1989. No, Virginia, there is no pear, plum, apple, apricot, or any other non-grape grappa.

The folks at Nonino know the best grappa comes from the best grapes, and they specialize in using single varietals in their process, and in using only fresh pomace. The pomace all comes to the facility immediately following the wine fermentation, over just a two-month period, so it all happens at once. Some places freeze the pomace for later use, but not at Nonino.

Up until 1973, all the different pomace went into the same fermenters, but at that time the Nonino distillers decided to separate varietals, creating an assortment of nuanced grappa. Thus the long row of fermentation tanks in the picture above, into which the pomace goes immediately — within one hour — of its arrival at the facility.

This pomace still contains yeast from the wine fermentation, so the transformation of sugar to more alcohol takes no more than five days. Still, they need to work quickly to get the successive batches in the fermenters.

Then it’s time to distill, distill, distill. Each of the tanks on the left cooks — with easily controlled steam — the fermented pomace, from which 480 kilos in the distiller leads to about 25 liters of grappa. This, of course, depends — white grapes give less, and Merlot gives more, for example. The alcohol travels through the pipes to the distillation columns on the right, and then the vapors condense to liquid. And that’s where the real magic happens.

You remember from high school chemistry all about distillation, right? Maybe not. The important thing, I’ll remind you, is that different liquids, like water and alcohol, change from liquid to gas (evaporate, yes?) at different temperatures. And of course it’s not a distinct temperature, there’s some overlap where multiple gases mix together.

Not all alcohols and aromatic substances provide a pleasant drinking experience, to put it mildly. We do not want those mixed liquids.

So the Master Distiller needs to switch the value to eliminate the first and last parts — the head and tail — and keep the best, middle part — the heart, the only part that really matters. This is grappa. They are Masters for a reason, and with enough experience, they do it by feel alone.

If you don’t do it right, you end up with something akin to what I “enjoyed” in Raleigh. If you do it right, you get something much, much better. It’s magic.

(There’s an interesting contraption in the process that precisely measures how much salable alcohol is produced, so the Tax Man can not only collect his share but also track exactly what is produced, and where it goes.)

The heads and tails still serve a purpose, though, and are sold to be made into industrial cleaning solutions. Some leftover pomace goes back to the vineyard for fertilizer, and some is sold as animal feed. But it can also be dried, ground, and made into a gluten-free flour to become bread.

Now you’ve got some grappa on your hands (or hopefully in a glass). This is “young” or “white” grappa, and might be bottled right away, or aged in steel or glass vats. It’s colorless (no matter the color of grapes), and should have a clean, delicate flavor.

Or, if it’s monovarietal, made from a specifically aromatic grape — like Moscato or Merlot — it will become a more flavorful grappa, with a perfumed aroma.

Young grappa can also be infused with fruit, roots, herbs, and other plant matter to produce aromatized grappa, which may lead to herbaceous flavors like a gin, amaro, or appertivo.

Other grappa might be aged in barrels, pictured above. The oak casks give it a pale straw color and more distinct flavors, similar to bourbon or whiskey.

Orazio Nonino founded the Nonino distillery in 1987, and it has been a family business since then. Silvia Nonino took charge of the distillery at the death of her husband in 1940, and she and later leaders introduced single varietals, appertivos, and other unique bottlings.

A standout story among many in the distillery history started in 1975, when the Noninos discovered some of their most important grapes — like Schioppettino, Tazzelenghe and Pignolo — were not listed in the European Community list of Friuli cultivars, and thus it was forbidden to grow them, or at least to name them on the bottles. To get these grapes them more recognition, Nonino launched a contest, the Nonino Risit d’Aur Prize, for the vine grower with the best plants of these vine varieties, and introduced a scholarship to go along with it.

Giannola also sent off letters to the appropriate officials to secure the listing. Eventually, the story goes, she sent to one particular resistive official a bottle, with a note: if you like this, sign the paperwork!

In 1977, by Ministerial Decree, and in 1983, by EEC regulation, the vines were officially authorized, and are now the flagships of Friulian vine-growing.

This woman knows how to make things happen. So it should be no surprise that even at 86 she still makes sure there’s always a bottle of Nonino in most any photo with her. Under her leadership and that of her growing family, Nonino has earned countless awards and honors.

As with anything you drink, or eat, use all five senses when you experience grappa. First, use your eyes to see the color, or lack thereof. Then your nose, to sense the aromas. Then take tiny sips to feel, and taste — be sure to breathe in and out of your nose, because flavor comprises both taste and smell.

But most importantly, listen carefully to what the grappa is saying to you. A well-made grappa from a master distiller may tell you the story of the distillation process and the nearly spent grapes that still had more deliciousness to give. And a Nonino grappa may also tell you about the tradition of quality and innovation and perseverance going back to 1897.

###